|

Core Area 3: The Wider Context: Understanding and engaging with legislation, policies and standards.

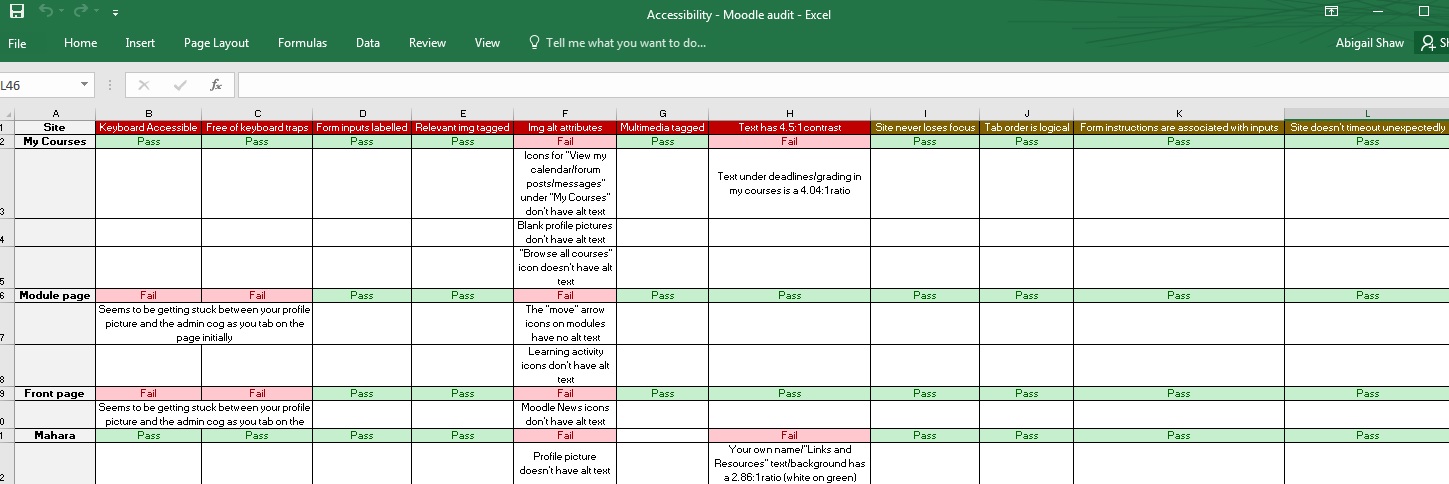

3a) Understanding and engaging with legislation.Description:In my previous institution, in 2019, in advance of the public sector legal requirement to ensure the VLE adhered to Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 I and my colleague carried out a full VLE audit, identifying issues and practices which did not meet these guidelines. (Evidence 1: A screenshot of my draft Accessibility audit (final version internal-only)). This audit not only resulted in the updating of much of our practice and guidance, but it also served to familiarise me with the working practice of implementing accessible design in the VLE. My previous institution was bound by this legislation but the nature of my current institution means that, unlike many UK universities, it is not. The Public Sector Bodies Accessibility Regulations Act of 2018, the legislation most commonly-cited legislation in recent UK Higher Education pushes for accessible digital content, is not specifically applicable, and this is something of a known fact in the institution. This technicality had led to something of an academic disengagement from the pursuit of accessibility, and a number of institutional initiatives to improve this were put on hold at the point of ERT. Whilst students with stated disabilities are, in my institution, in possession of a “Statement of Reasonable Adjustments”, which include a series of requirements for that student that must be met, these tended to focus on the immediate requirements for students in live sessions – transcripts, note-taking, and suchlike. However, this requires students both to know of, and to disclose, disabilities. There has, to date, been no Faculty-level support and guidance for accessible digital education. My institution recently brought in a new Head of Accessibility for Digital Education, tasked, in the first instance, with updating institutional Digital Accessibility Policy, and, as I was keen to move forwards on working on this in my Faculty, I invited them to speak with myself and fellow FLTLs on how we might be better involved in the creation of this policy. Here, they offered a particularly useful point, which was that, whilst my current institution may not be bound by the Public Sector Bodies Organisation Accessibility Act of 2018, it is certainly still bound by the Equality Act of 2010, which states: (2) The responsible body of such an institution must not discriminate against a student—

Equality Act (Section 91, 2)This unarguable obligation to produce accessible core content and resources was, I felt, the leverage required to make some headway on prioritising accessible digital content at Faculty level. Further, as accessibility had come up in a recent piece of Faculty-level research I had carried out with Arts & Humanities students (discussed at length in Specialist Area 1), I knew that it was important to our students. These two factors together, I felt sure, would cement its importance to our academics. I created 3 sessions for module leads ahead of academic year 2022/23, and centred the second of these on Accessibility. I asked our Head of Digital Accessibility to reinforce and expand upon the impact of considering the Equality Act in terms of digital education. This session was recorded, to provide a future resource for A&H academics (Evidence 2: blog post containing links to session recordings, and resources). When I conducted academic online research in 2020/21 (referenced in more detail in Specialist Area 1) I gave academics the chance to anonymously share their thoughts and experiences around online teaching. One element that came up more than once was a lack of clarity about what being accessible meant in literal terms – that the area seemed messy, and complex, and there was a fear of the legislative consequences an academic might have by not understanding a supposed truth of accessibility. The new institutional policy, to which I have contributed both in content and as reviewer, will further support and facilitate my ability to improve understanding and practice of this legislative compliance by developing Faculty-level resources with discipline-level specificity. I have continued to engage with the Digital Accessibility team to attempt to clarify and support the types of central guidance that are given. Evidence 3 is an exchange in attempting to support a programme required to record content for a student with SoRA who had been asked to use a particular piece of software which was not easily available to them, as it was not located in their teaching rooms. This issue arose as a result of a misunderstanding at the Student Services end about the names of the platforms available and the limitation of small group teaching rooms – when the programme could not use the named software, they were very worried that they might be breaking a legal requirement by using an alternative. Whilst the extent to which this might have been the case is debatable, the background point was well made, and I have encouraged us to revisit SoRA guidance collectively to ensure that it can be applied as widely as possible, utilising all available tools. Evidence 4 is an extract from the minutes of the Digital Accessibility Working Group, another institutional group I regularly attend and contribute to, demonstrating again how I am looking for clarity regarding institutional guidance, and supporting colleagues in understanding where the complexities lie in the conflicting provisions for some legislation. In this instance, copyrighted content being unable to be stored within our own institutional platforms, leading to a discussion of the best ways for this content to be linked to and included in recorded sessions. Reflection:Many of my colleagues were unaware of the specificity of the Equality Act 2010, and were understandably keen to improve and support their students in line with its requirements. I have had good engagement with both the live session and the subsequent blog post and resources, and will continue to create such things – more of which in Section 3b. The opportunity to collaborate in this session with the Head of Digital Accessibility, and have them directly communicate and disseminate information to my colleagues was very well-received. The Faculty senior leadership were also pleased to have such input from senior central teams, and boosted my invitation to academic colleagues which, I think, supported its importance and improved buy-in. I work so closely with senior central figures that I forget sometimes that my Faculty can feel quite separate from them – if, indeed, they are aware that these central teams even exist – and I feel that joining the dots between these teams and my Faculty is an area where I can significantly improve our ability to engage with legislation in practice. Maintaining a strong connection between FLTLs and the Digital Accessibility team seems a vital component of ensuring we comply not only with legislation, but that we do so in a sustainable, considerate, and intentional way. The ways in which we institutionally engage with accessibility legislation appear to me to be an important area for me to feed back regularly, not least as a result of our students in specialist disciplines, such as in the Art School. Keeping abreast of institutional, and sector-wide conversations around this is vital for my role, and the specialist working groups at my institution are a useful way for me to do this, as are the ALT, M25 and other learning technology communities, where matters of accessibility, amongst other legislation, where experience of best, common, and complex practice is keenly sought. This is also an area where I would be interested to communicate further with other digital education specialists in the Arts & Humanities – I am actively looking to attend conferences that discuss these issues in particular in 2022/23. Overall, my main focus here is to support engagement with accessibility by encouraging my academic and professional services colleagues to approach all teaching and learning creation with an holistic, inclusive design mindset, whereby all students can access their teaching and learning in the way that best suits them. Obviously such broad-strokes sentences are, I’m aware, the very kind that can spark concern and anxiety, and my role is in part not to have to use those sentences at all, but rather to illustrate with my work, the guidance I provide, and the tools and processes I recommend and embed across the Faculty, a default setting that can be as supportive of students with additional requirements, and/or disabilities as possible, whilst also, of course, complying with external legislation, and institutional guidance. Evidence:1. A screenshot of a draft of my Moodle accessibility audit:

2. Blog post containing links to Digital Accessibility recordings and resources: https://reflect.ucl.ac.uk/abbiwrites/2022/09/26/digital-accessibility-ah-module-lead-teaching-admin-session-2/3. Extract from an email from myself to a group of colleagues working on clarifying academic guidance around recording content for students with SoRA:I would agree with [colleague’s] changes and think that this should clear up some of the issues arising. Whilst Echo360 is functional for the job, there are plenty of other options, and, especially in A&H, there are comparatively few Echo360 rooms used for regular teaching. I think we may need to have some clear direction for academics regarding available support for this, signposted along with SoRA delivery, as a lot of the more frenetic responses are from misconceptions around the recording method and distribution (e.g. unaware that it is easy enough to share recordings just with students who require them, rather than making available for all) – perhaps we might meet with FLTLs etc towards the end of the month to look at this? Extract from a response to the above:Dear Abbi Many thanks for this. I think it is a great idea for us all to meet to discuss further signposting and support via the SORA in a meeting with FLTLs. Please count me in. I think we could also discuss the best guidance to add to our Towards Inclusivity document too as part of this. 4. Extract from minutes illustrating some of my contributions to the institutional Digital Accessibility Working Group (AS = me):

References:Equality Act of 2010: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/part/6/chapter/23b) Understanding and engaging with policies and standardsIn this section, I would like to illustrate my engagement with the institutional IP policy. My previous institution had an extremely firm policy on Lecture Capture, and as part of the creation of that policy, a robust and firmly-constructed IP policy, the creation of which I worked on extensively. Description:When I began at my current institution, I was surprised by the prevalence of myths and anxieties around recording teaching and learning content. In my Faculty, this practice had been rather rare, and, until ERT, it had been accepted as something that was not particularly relevant to the institution at all. As a result of the predicament of international students during ERT, however, it became part of the institutional Temporary Operating Model to recommend recording lectures, at least, wherever possible to support and enable students outside time zones, or with caring responsibilities, or indeed with illness, or other complexities arising from ERT to access their teaching and learning as easily as possible. This recommendation panicked my Faculty, and this panic was such a different response to the practice I was used to that I was keen to take the time to unpick this and understand where the fear had come from. I was regularly told, for example, that academics should not use the institutional video recording platforms as, if they did, anything they had recorded in them would automatically belong to the university. The current workaround colleagues were recommending to each other was to record content on their mobile phones, and either then uploading it into institutional platforms (a wholly unproductive, and unnecessary difference), or to put it on an external video platform, and send the students their link. This practice I was extremely keen to put a stop to (not least for accessibility purposes, both with regards to disability, and with regards to country restrictions on online platforms), and so I sought to uncover the roots of this, I was sure, misconception. I searched the institutional intranet for IP policy, and the most recent document I could find was from 2018. It seemed predominantly to deal with the structure and details of teaching in the VLE, such as course outlines and contents, and then to the recorded content that had been recorded by AV teams (e.g. conferences, guest speakers, broadcast events). Neither of these seemed to capture the nature of recorded lectures and asynchronous content, and, on examination, I could see how my colleagues had come to feel that using university platforms would result in a loss of any and all IP rights to their recordings. Whether or not they would have these rights was a concern I was not sure I could resolve myself, but what I did feel I should be able to secure for my colleagues was an institutional understanding that their content would not be accessed without their consent, and would not be re-used by others. I raised this issue in a central Digital Education meeting, and was asked to put the concerns down in writing and progress accordingly. Evidence 1 is an extract from an email outlining this. I was asked to attend several further conversations with those working on the Temporary Operating Model for the forthcoming year to continue to represent my Faculty concerns, and I was pleased to be able to do this. The upshot was a slightly reworded section in the new Temporary Operating Model which did go some way to assuage academic concerns. In the meantime, I had realised that a lack of familiarity with the tools and practices around creating and sharing recorded content could be exacerbating the academics’ anxieties. I spent quite some time working with Connected Learning Leads (each department’s nominated digital education representatives) to “myth bust” and show them how the best ways to place recorded content in Moodle. Once the process was shown to them within a space as familiar as the VLE, it seemed to somewhat reduce some of the fears around these things. Demonstrating that content could not easily be removed from the platform also helped, and once I realised that something academics were really concerned about was students sharing recordings on social media, I realised I might be able to at least quell that anxiety. Eventually I found, in the Student IT Policy, a commitment that students must not remove, or share, institutional teaching content – including video that either they, their academics, or the institution, has taken. Sharing this widely with academics – and encouraging them to make their students aware of this fact prior to sharing recorded content with them proved to be extremely useful. One of the more interesting points an academic made about this was when they mentioned that they hadn’t really thought about how students could, at any time, have been recording them in lectures in person anyway. The meeting at which this was discussed reflected on this at some length, and seemed reassured that, not only was it not something students were permitted to do, somehow, it hadn’t already happened to them (at least as far as they knew – and even there, they concluded that if they didn’t know, it was probably okay!). I continued this conversation at as many points as possible – evidence 2 is an example of my contacting one of my academics who expressed concerns about IP policy in an institutional Town Hall. As the CLLs started to support their colleagues in using video content, it seemed that increasingly academics became less resistant. This was also supported by their students’ enthusiasm for the model. Our Faculty-level Student Online Experience research showed overwhelmingly that students appreciated recorded content, and many academics reported results from using it such as students being more familiar with core concepts, or appearing to have a better overall grasp on their subject. In an attempt to ensure I had some more evidence to support me at the next round of institutional-level conversations, I captured what I could from my Academic Online Experience report – evidence 3 is an extract from this summarising comments mentioning concerns around IP policy. This report, which had some traction amongst institutional senior leadership, was again used in conversations around the Temporary Operating Model for 2022/23, and IP policy was held as it had been the previous year, as it seemed to have been working. However, the institution continues to struggle with updating its IP policy overall, in part because it rarely wishes to take a strong position on one methodology or another. I will continue to capture thoughts about creating recorded content and lectures from academics and students alike, as, increasingly, recorded lectures, or extensive use of the flipped classroom, are the norm in UK HE, and I suspect we will start to see even more student calls for this type of content. In order to meet them, we will need a robust, and mindful institutional IP policy. Reflection:This policy area was a huge contrast for me between my previous and current roles. I uncovered so much about my Faculty from examining their attitudes to this, and also realised how poorly-disseminated institutional support and guidance had been. Taking steps to address this exposed me to numerous people and resources that were extremely useful in my later practice, that I would otherwise have taken significantly longer to find. Having such a thorny issue to unpick with CLLs gave me a really useful way to demonstrate my own experience and understanding, and it also allowed me to make room to listen to their concerns. Even where they weren’t my own concerns, I was pleased to be able to demonstrate to them that their concerns were my responsibility, and where I had been able to make representation of these at higher levels, this was very warmly received. This also demonstrated to me how important policy is for practice: it is something that we can lean on, define ourselves by, gives us boundaries that we can work within and point at where others might ask us why we do things in a particular way. These boundaries are important with technology, not least because the fear of technology, and the power of something like a recorded clip of an academic saying or doing something, has never been more prevalent. Where the institution was unable, or unwilling, to define its approach to teaching content, this had sent a message to some academics the institution did not necessarily value them and their teaching as something to be protected and appreciated. I have tried to support my Faculty around engagement with this policy in a variety of ways, from resources, to information, to teaching them about the ways in which they might use things, but I don’t know if anything was quite as effective as my moving to engage with the policy itself. There had been a very passive approach to the previous IP policy, as something that was simply put upon them that they did not necessarily have any recourse to. Even when academics had written against it amongst each other, it had seemed that they would come up against one barrier or another when trying to work out how to get to those who were actually responsible for it. That I was willing to pursue this and represent their thoughts to senior central leadership again contributed to my Faculty goodwill, and relational trust. Evidence:1. Extract from an email to a senior leader in Digital Education, outlining academic resistance to the current IP policy, and its consequences:Point 1: re. IP policy and licensing: Clarity is requested around 2.1.2 “The university agrees that copyright in scholarly materials and teaching materials shall belong to the staff member who is the author/originator of such materials, except where those materials fall within any of the specific categories referred to in section 2.1.3” with the issue in question being 2.1.3 (e) teaching materials which are specifically commissioned by the university…for example…a MOOC or other online programme delivery and (g) sound recordings, films and broadcasts created for the purpose of teaching, where the university has made the necessary arrangements [my emphasis] for the making of the sound recording, film or broadcast (as the case may be). As a consequence of Point 1…Point 2: Some academics believe creation of audio/video content using university accounts, university-provided software or institutional platforms (specifically Echo360) will result in the content being identifiably* the intellectual property of the university, leading to strange workflows such as purposefully creating content in personal software and then at some length uploading it into platforms in which they could simply have created the material in the first place. *I have covered the fact that a video file is a video file, etc. and that there is no fingerprinting or internal marking – the principle of the concern remains… Point 3: From __________ 10/08/2020, “Operational Update issue 37…” “Academics own the teaching materials that they create in the course of their normal duties, except in the case of certain categories of material, which includes film and sound recordings…In order to allay these concerns, [Institution] commits, notwithstanding the position in the Intellectual Property Policy, not to use teaching-related film and sound recordings created during academic years 2019/20 and 2020/21 without the originators’ consent.” This may well be covered by the union reps: the academic concern is a) whether this will be extended b) where the emphasis falls, i.e. will only content created during these academic years be protected and protected in perpetuity, or will the content created specifically during those academic years only be protected until 2021-22, when it can be used at the institution’s discretion (including, say, during strike action). Do let me know if you have any further queries around these; I hope I’ve represented the concerns clearly, and that any forthcoming policy can either remove or address them in such a way as to inspire more confidence from the faculty. 2. An extract from an email to an academic concerned about IP policy:“I hope you don’t mind me immediately contacting but, I’m glad you brought up the IP rights and concerns around striking with pre-recorded content just now – I’m working on encapsulating these at local level (without identifying individuals, rather, sharing a Faculty Concern) and feeding it to the group now working to define policy and documentation for Echo360, recorded content and so on for Term 2 and the updated Temporary Operating Policy. Please do share any nutshell comments or concerns you would like me to pass on to _______________ directly; I will be happy to do so. “ 3. An extract from my Academic Online Experience report relating to IP concerns:Other concerns were raised in relation to intellectual property (IP) and institutional use policies: “I have deep concerns about how universities could exploit workers through appropriating their recorded materials. There are pledges in place regarding this, but I still worry that universities unintentionally (?) drift towards exploitation over time.” [60, (?) in original]; “I am concerned […] about labour issues if these lectures are being re-used when the original creators are no longer being paid.” [37] The issue of IP policy with regard to recorded video was not new to the Faculty for 2020/21, and whilst many academics have commented positively on the use of video for teaching now that they have had experience of it, some participants are already mindful of the complexity of the issues ahead of its continued use: “We need a proper debate about the future for this kind of technology. Unfortunately management wants to control IP, and staff will want to retain control, so the debate becomes unnecessarily polarised.” [38] |

|||

|