|

Core area 2: Learning, teaching and assessment

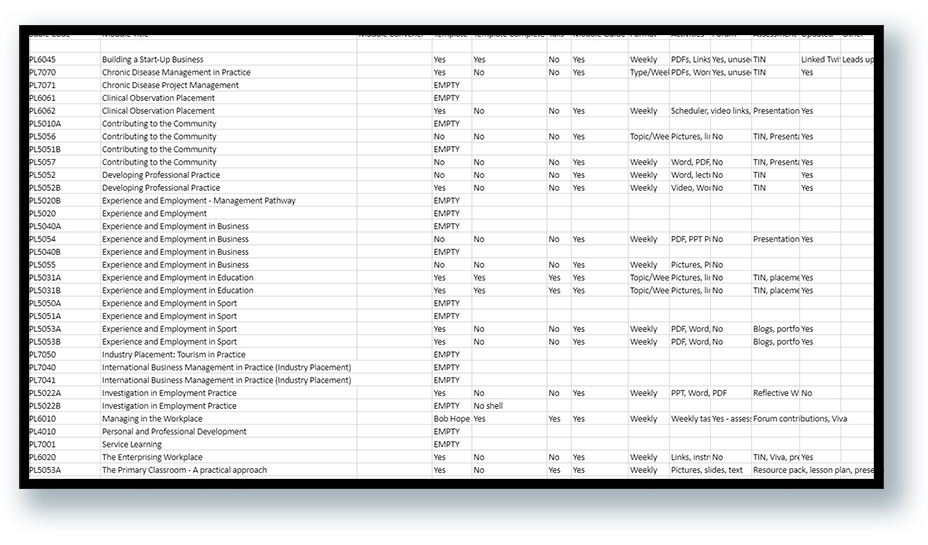

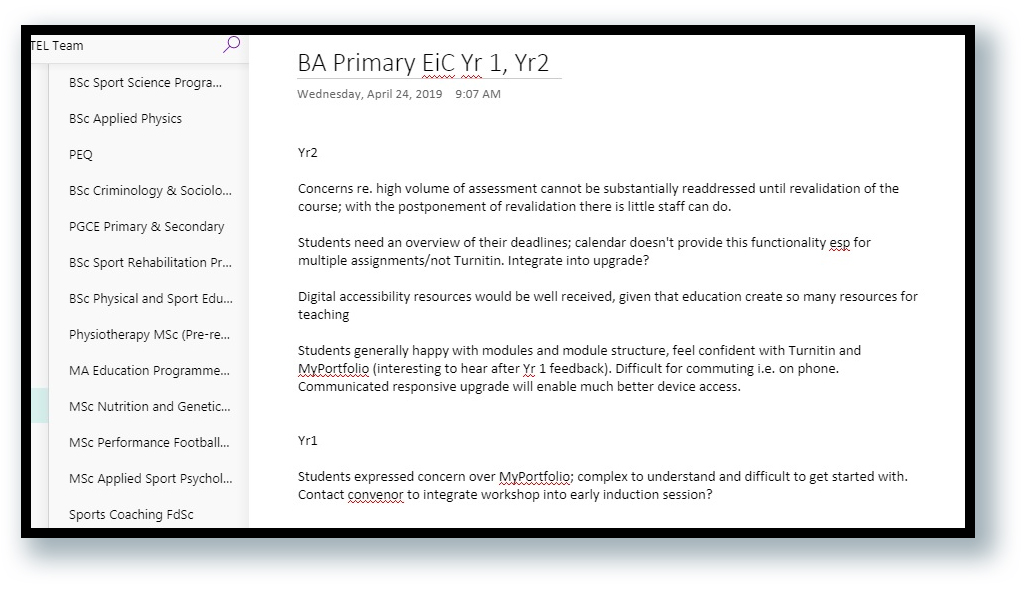

2a) An understanding of the teaching, learning and assessment processI achieved my Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy in January 2020 (Evidence 1a), demonstrating my support and understanding of teaching and learning for this in multiple ways, including with the support and training I provided to staff, my contributions to programme development, assessment design, and work I did across the institution to improve feedback delivery and workflows. This professional portfolio also included a Teaching Observation (Evidence 1b), which gave me a great opportunity to reflect on my delivery, the structure of my sessions, and my skills as an educator, all of which I would come to draw on in the work outlined in the rest of this section. To exemplify my understanding of teaching, learning and assessment, and my contribution to its technological development at my institution, I would first like to outline my part in the development of an institutional Moodle template. In the second part of this section, I discuss the deployment of this template, including my experiences designing and leading training sessions with academics. My contributions included an audit of existing Moodle use, the compilation of feedback and observations obtained regarding the existing use of technology for teaching, learning and assessment, and using population of the template itself to embed confidence in the new setup and encourage best practice in every area of teaching and learning via mandatory training for every member of staff involved with the VLE. I further provided induction support to returning students, gathered more feedback on the new structure and templates, in order to evaluate our process and design, and to ensure our new foundations are as solid as possible as we move into the next phase of development. As evidence, I attach (2) a screenshot of a section of my Moodle audit (3) an example of notes of issues raised at a programme board (4) screenshots of the Assessment Overview section and the new template in action and (5) feedback on and verification of the contents of one of my Moodle training sessions from a Programme Director (Evidence at end of section). At the end of this section, I look back on this project from the perspective of my current role in 2022, reflecting on its outcomes, and the ways in which it continues to shape and support my leadership in learning technology. Description:My institution adopted Moodle as its VLE back in 2013, but it was not a requirement for every course to use it until 2017, when the university made it mandatory for all text-based work to be submitted via Turnitin, and for every course to house its module guide and basic information on Moodle. As significant institutional change took place during 2018, including a large staff turnover in every area, investment in terms of both time and resources was fairly low, and unless staff were either particularly interested in providing robust online resources, had experience from a previous workplace, or had good Faculty support to hand, it was challenging for them to make the most of what was a very basic Moodle setup. Moodle had never been consciously skinned or designed for the university, although a pre-existing working group had created a template that was meant to be used in every module to provide consistency of information. My colleague and I suspected that this was poorly used, and undertook a comprehensive audit of modules to assess the extent to which this was the case. This audit showed that it was not only the case, but that the template was very rarely completed at all, often populated with broken links, and that often "DELETE WHEN COMPLETE" text put in as a placeholder was often still on show. We spent some time gathering comments and complaints on the existing setup via our user forum, programme team meetings, and informal conversations with staff, including:

With the staff here as our learners, we felt that, in order to fully engage them to the extent required, we would have to give a solid pedagogical case for the new look and template, and to ensure they felt the training they would have to undergo would be relevant, accessible to all levels of digital capability, and easy to explain and adapt to each course's requirements. It seemed little attention had been given to explaining Moodle as a tool for learning delivery, rather than as a thing-in-itself, and our goal was to go from 'using Moodle' to mean, literally opening it and putting things there, to meaning, developing the module, from content to delivery to assessment, to embrace the platform and its capabilities entirely. Our goals were:

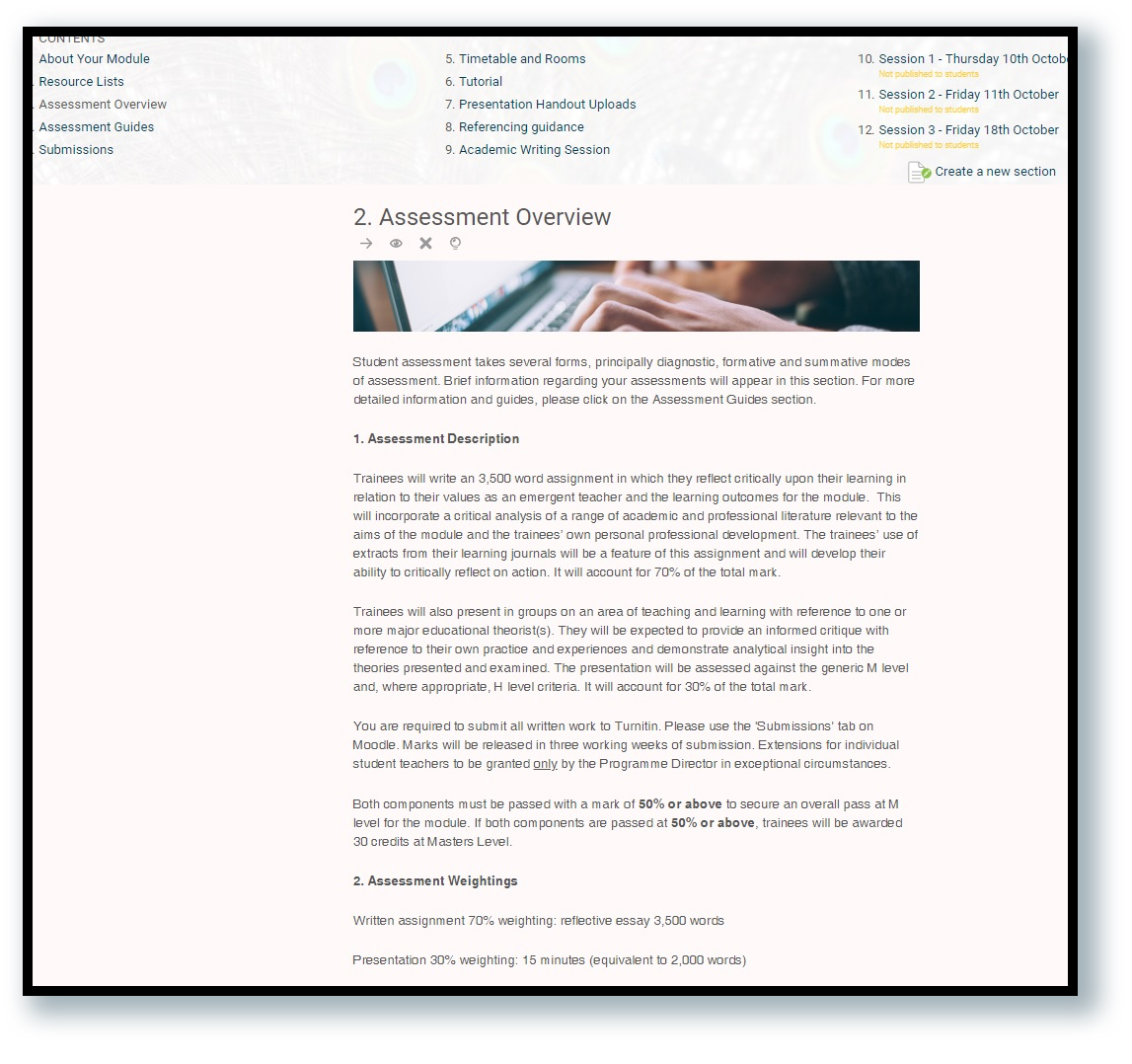

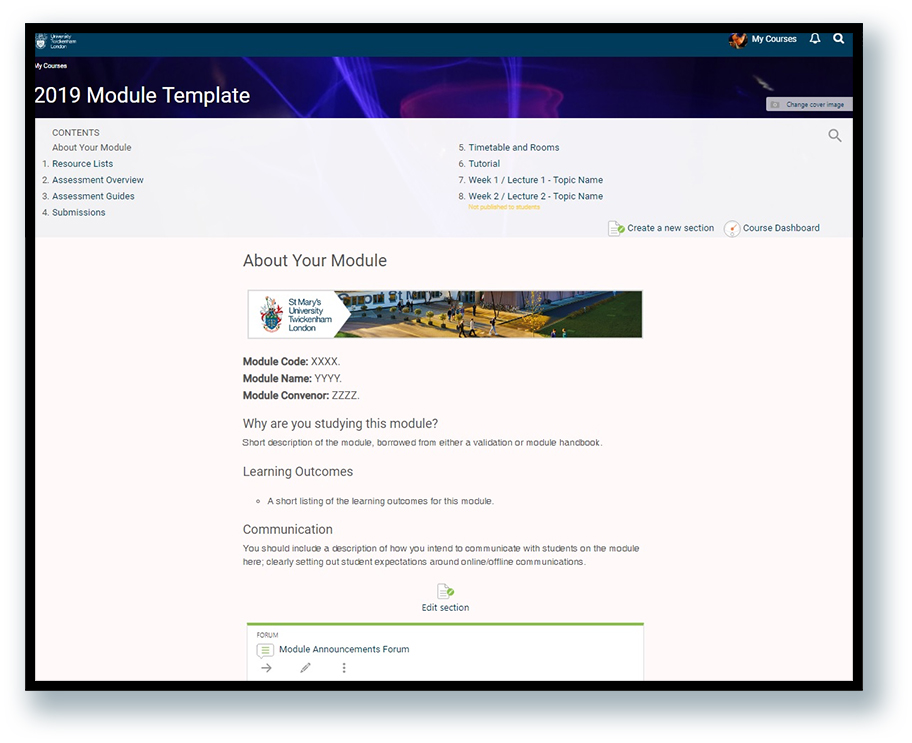

We based our template design on the RASE model (Resources, Activities, Support and Evaluation (Churchill, D., King, M., Webster, B. & Fox, B. (2013)1) as, we felt, common across the university was a lack of knowledge about how best to anchor these elements in technology, and the RASE model provides a student-centred, outcome-driven method for structuring modules which encompass any number or type of resources. The perception of Moodle was that it was a repository for resources, and/or a location for online inboxes. A few courses had done some interesting work with available activities - one particularly interesting distance course used forums for all interactions, and for a series of discoursive assessments, which made for a fascinating case study - but most were collections of PDFs and PowerPoints with a single Turnitin assignment at the end, with very few displaying any intentional, progressive or conscious learning design elements. The first page of the template (About your module) lists Learning Outcomes for that module, just as RASE development stems from contemplation of intended learning outcomes, and this page also includes "Why are you studying this module?" designed to explain how the module itself fits into the student's programme of study (again, a core part of RASE). Often, and perhaps because our Moodle site has no hierarchical structure, rather all modules appear on a level, including the student's programme module, students felt their modules did not have a particularly clear identity, especially where two or more modules were taught by the same member of staff. As students always land on the 'about' page, they will consistently be greeted by their Learning Outcomes, and, even if it's only with repetition, there is the hope that they will consistently understand the value of each specific module as they navigate through. I was responsible for developing the Assessment Overview section of the template - a common, and widespread comment from students across programmes was that they found it difficult to know how and when they would be assessed. In the previous structure, this information was contained in the module guide, which was often lengthy. It was displayed in Book format, which students either didn't notice, owing to the tiny icon it generated, or which they found difficult to navigate if looking on a device, and the format included all the guidelines for each assessment, making it difficult to pick out the core points. In one particular programme board, students had struggled so much for clarity regarding how and when they would be assessed across their modules, as they were a group only present on campus one day per week, with an unusually, but unavoidably, large clash of deadlines across multiple modules, they asked if they could somehow have an overview of this. Our Moodle calendar does not pick up assignments particularly well, especially if they aren't Turnitin ones, and students have struggled to use it, so we were reluctant to try and channel them towards it as a solution. I saw the Assessment Overview section as an opportunity to place this information straight into students' hands: they could see, at a glance, how they would be assessed for each module, and would have a single, easily accessible point of truth for the times, nature and weightings of their assessments. Throughout our training sessions, I emphasised the importance of completing this section clearly and accurately in advance of student enrolment. During the implementation phase, where academics were working on their modules prior to releasing them, I was pleased to see this completed in every module without exception. Then, in induction, I went to the new cohort whose predecessors had had so many issues with their assessment deadlines and emphasised the section and need to prepare, long-term, for their deadlines. I also suggested, as I have done to all new cohorts whose predecessors struggled with deadlines, that they create a physical calendar for the academic year (or picked up one of the Student Union ones) and, right at this start of term, put their deadlines on it, rather than relying on digital reminders. I will evaluate the effectiveness of this section by comparing the students' comments at forthcoming programme boards and in their mid- and post-module feedback. I have already had positive feedback from students on multiple courses who have found this information useful, and staff have stated that they find it useful to have a dedicated space for this information. We decided as a team that, as this would be such a major upgrade, it would be that rare time we could insist on mandatory training for all staff, on all programmes. This gave us a tremendous opportunity to tackle the widespread inconsistencies and poor practice, but required us to come up with a method of delivery that would be as foolproof and flexible as possible. With a good, mandatory template, we thought, we could embed the keystones of good learning design, and, by making our training sessions additionally a hands-on opportunity for staff to begin populating their modules, we would be able to get staff started right then and there, and use the process of populating the template to introduce how one worked on the system in the new theme. Our sessions were consciously designed, 90 minutes in total, and held in a computer lab. The first 45 minutes consisted of an introduction to the new look and design, but was also bespoke to each programme, deliberately presented around the most relevant points to their National Student Survey comments and programme boards, with the latter 45 minutes for staff to get to grips with populating the new template and importing content from previous years with our on-hand support. I have one other Learning Technologist colleague, and we took turns to lead sessions, delivering up to 4 sessions per day. We predominantly led sessions with the faculties we had worked with, and took time to engage with the programmes' existing modules beforehand and brief each other on any issues we were aware of that would be tackled by the introduction of the template. Reflection:This has been, by far, the most positive experience I have ever had of introducing technological change to any institution. Staff and students alike have been hugely positive throughout the process. We had excellent attendance at our training sessions (not a given, especially as, for some programmes, this was held during a particularly busy period) - we managed to see over 180 staff in 38 hours of training over the course of ten weeks. We are in the process of developing evaluations for the success or otherwise of our new theme and template design, but early feedback has been enthusiastic, and throughout the induction period, staff and returning students alike have reported significantly fewer issues than this time last year with regard to finding and using resources on Moodle, and have expressed appreciation for the new look. I am creating a case study for this project, in which I hope to compare activity engagement statistics between this year and the last, as well as usage statistics, comments in programme and module evaluations, and the extent to which any reported issues over the year relate to, or could be addressed by, the VLE, compared with the previous year. I was grateful for the amount of background research and that I had been able to keep students' programme board feedback in mind throughout the development of the upgrade. As we worked with each department in turn, it was possible for me to directly relate the feedback from students on their specific programmes to the changes made. By informing academics immediately how the system upgrade had been done with, specifically, their students in mind, elicited hugely positive reactions every time, and it seemed to ensure that even those who weren't that interested felt that it was worth their effort, as they clearly understood why the changes had been made, they felt that these changes would positively affect both their teaching and their students' learning, and they could see why proficiency with the new setup would be productive for all concerned. If I were to go through this scenario again, the main thing I would change would be my approach to the few colleagues we could not get to the programme group training. Some were reluctant to undergo any training at all, describing themselves as "good with computers", but as a core part of our delivery was to introduce the conscious learning design element to staff, we did insist on meeting them. However, I was not able to workshop my way through the template with them effectively, nor to fully embed the RASE model in my explanation, and, invariably, they all came back to us at multiple points in the days leading up to the start of semester with questions that would easily have been covered in a full session, taking up valuable time and resources to a less-satisfactory conclusion. It was also not particularly easy to engage them with the specifics of the template for their programme, as any negative feedback that would be resolved by the new structure was harder to discuss on a one-to-one basis than with a full programme of staff, who were universally willing to tackle such issues. This experience validated our choice to hold group training - where I was able to fully communicate why we were introducing change, and how it would be useful, it was easy to maintain interest and staff were keen to embrace and engage with the practical part of the session. Where the setup was not present, the interest in seeing the training through was hard to maintain. Next time I would make a significant effort with programme directors to arrange a time when all staff were able to attend, and then, if there were still staff who were unable to come, rather than offering one-to-one catchups, I would instead suggest we hold scheduled wash-up sessions to ensure some peer interactivity and, hopefully, engagement. Crucially, this issue was a vital pedagogical lesson for me - personally, a very solitary learner - regarding the difference between group learning, and individual tuition.I had previously assumed that one-to-one sessions would offer the opportunity for greater depth and reflection, but significantly underestimated the space afforded for personal growth and development in a group setting. During the workshop sections of our training, where academics had the opportunity to experiment with the new theme and templates in a 'safe' space, with someone present to fix anything they did manage to break, many of them were comfortable testing and expanding their knowledge in a way they were not, where they felt they were being 'watched' all the time. This also exemplifies a core lesson for me, from this, which is that change is only as good as its implementation, and that, when trying to encourage good teaching and learning practices, one must engage in them oneself. Technology is as apt to quash enthusiastic teaching and learning without robust guidance and support as it is to enable it to thrive, and in my role as a learning technologist, this was a wonderful opportunity to provide technological boundaries, structure and development for the excellent teaching and learning that takes place at my institution. 2022 update and further reflection:This project was enormously rewarding for me, and gave me confidence in managing large teaching, learning and assessment challenges – confidence which was vital with my current work, in projects such as the Wiseflow adoption for the Art School (discussed at length in 1a. and 2b.) Knowing that genuinely, evidence and experienced-based changes to practices and workflows could, when fully and firmly justified to academics, be warmly received helped maintain my motivation when experiencing resistance in later paths. Further, when Emergency Remote Teaching began at short notice in March 2020, my previous institution was, as a result of this overhaul, and mindful redesign and discussion of Moodle, in an excellent position to move teaching online with minimal disruption. Spaces such as the Assessment Overview enabled students to easily understand any changes to their assessment as a result of ERT, minimising anxieties and maintaining a sense of clarity and continuity. I have also maintained my interest in working with academics collectively wherever possible, when introducing them to new technologies and methodologies – as this was a core part of my role at the moment of joining my new institution, I was grateful to be able to draw on this experience when planning my early engagement with departments. One example of this was in creating bespoke training for departments to ensure that their chosen method of online teaching was correctly set up (Evidence 6: Greek & Latin departmental Zoom training). Harnessing academics’ existing relationships and inherent peer support structures helped me ensure that the departments felt collectively enabled, as well as individually, as well as minimising that need for repeated individual conversations I had noted before. My experience with the Moodle redesign project became the catalyst for my development into a more strategic, leadership role, acting pre-emptively and collectively, in ways that can be scaled as required. Overall, this was a highly formative project, whose reflections have continued to firmly ground me as I progressed into my new role. Evidence:1a. AFHEA Certificate

1b. Teaching Observation and Reflection:

2. A screenshot of a small section of my Moodle modules audit:Click to view:

3. A screenshot of my notes from a programme board which prompted the development of a section of the new template:Click to view:

4a. A screenshot of the Assessment Overview section:Click to view:

4b. A screenshot of the basic, unpopulated templateClick to view:

5. Feedback on and verification of the contents of one of my Moodle training sessions from a Programme Director:Abigail led an inservice day for the MA in Catholic School Leadership team which covered the following key elements: Training on the new Moodle Module Page template which encompassed the following:

I would like to affirm unequally that the manner in which Abigail led the training was exemplary, embodying a teaching methodology which resonated with the classical reciprocity/mutuality paradigm, thereby enriching the learning experience of colleagues. Her pleasant manner and willingness to go “the extra mile” in support of colleagues resonates deeply with a generosity of spirit, a key characteristic of the distinctiveness nature of the ethos of St Mary’s University and one of its core values.

Dr John Lydon KCHS SFHEA, Principal Lecturer, Programme Director - MA in Catholic School Leadership 6. Greek & Latin Departmental Zoom Training: https://mediacentral.ucl.ac.uk/Player/HdICHJJIReferences:1. Churchill, D., King, M., Webster, B. & Fox, B. (2013). Integrating Learning Design, Interactivity, and Technology. In H. Carter, M. Gosper and J. Hedberg (Eds.), Electric Dreams. Proceedings ascilite 2013 Sydney.(pp.139-143) 2b) An understanding of the target learnersIn my original CMALT portfolio, I discussed working through a pre-registration module for Secondary PGCE students (Evidence: https://cmalt.aeshaw.co.uk/corearea2.html#b2). The feedback I received during this project, which forms evidence within that section, included a comment about how my understanding of learners shaped and had consequences for the academics running the course: it helped them to better understand their learners, and the shape of their course, too. I found the construction of this section to be a rather eye-opening experience, unpicking the way I approach a particular project has since helped me be more overtly methodical when working with departments defined by their institutionally-unusual students. I have since created a Case Study from this work, provided at the end of this section (Evidence 1). In my current role, the breadth and depth of specialism means that I need to be able to define the requirements of my learners swiftly, but accurately, and, moreover, to define the consequences of those characteristics for the technology, pedagogy and process in question. To respond to this section in detail, I consider the ways in which I needed to understand both academics, and students, as learners, in order to successfully deploy a new assessment platform to the Art School. Description:I was asked to find, deploy, and support a digital assessment platform for the Art School. In the decision-making process around the choice of platform (outlined in detail as my response to 1a. An Understanding of the Constraints and Benefits of Different Technologies), I identified that this project would require me to work with both academic staff and students, as learners, and that I would need to ensure my training and practices were closely tailored to the requirements and concerns of these groups in order to ensure that the assessments went as smoothly as possible. To summarise the nature of the assessment: every student in each year of the Art School needed to submit either a continuing, or a final portfolio of their work. Undergraduates and postgraduates had slightly different requirements, set by their relevant teaching committees. I was to offer training, consultation and support to all academics, all students, and, if required, to external examiners, regarding access, submission, and marking within Wiseflow, the platform chosen for assessment. The platform was new to my institution, and this use was a pilot case. I had good central support from the Project Team implementing Wiseflow, but there were a number of details in the setup that meant the majority of the workload around this was entirely my own, and this, as much as anything, meant that I had to work particularly hard to ensure academics, students and others were as aligned as possible. I had an opportunity, early on, to speak with the Art School student rep, whilst attending a general student rep meeting. Whilst brief, this informal conversation was an excellent opportunity to gather a single, early perspective from a student who was used to speaking on behalf of their cohort. They suggested that the previous year’s assessment had been extremely complicated, requiring students to follow very detailed and lengthy instructions, working, in many cases, across multiple sites to upload and submit their content. None of the constraints of the previous year would exist this year, and the process would be comparatively straightforward, but from this conversation I first came to understand that students who had submitted to the Art School in 19/20 had had a very stressful experience, and that they were, understandably, nervous at the idea of submitting such vital work online again this year. I went on to meet with the professional services staff who had supported the 19/20 assessments, and asked in detail about their experiences with the students. They recalled a lot of extremely difficult exchanges, large amounts of misunderstanding, and significant distress at various times, exacerbated, of course, by the sudden implementation of ERT, and the surrounding impact of Covid-19. A technician allowed me to see the platform used before, and to consider the assessment briefs. I found that, whilst clearly endeavouring to do their best, it was clear that the School had not had the support of a dedicated learning technology specialist, and had had very little time to work with students around the assessment. Finally, I was able to see the work students had submitted the previous year. The range of subjects, types, disciplines and methods used from a creative and artistic standpoint were revealing, and fascinating, and it was a privilege to be able to see the types, and quality, of work I would be supporting. I then met with the Head of School, who emphasised to me that one of the most difficult parts of this was that the digital assessment had, temporarily, at least, replaced the End of Year Show, and that this grand physical display of art was such a focal point of attending an Art School that the idea of this being “replaced” by digital assessment conferred a weight and anxiety that further complicated the student view of the situation. Students had an enormous variety of digital competence – from students who were extremely sophisticated in their use of technology, and would be submitting projects including code-based generative art, and 3D renderings, to those who struggled to log into university platforms at all. From this research, I understood that my teaching and support needed to be as reassuring, clear, specific, and accessible as possible. In several preparatory meetings, academics expressed concern about their peers understanding how to work with Wiseflow, and I was consistently warned that people would be “difficult” or “resistant”. I find difficulty, and resistance, to be some of the most characteristics of learners, as they are usually relatively easy to parse – learners who exhibit these tendences in the face of new technology rarely do so for the sake of being difficult (as I feel peers often think). Often, they have had difficult experiences where platforms have let them down, or a lack of training and understanding has resulted in their appearing, to their mind, foolish in front of their own students, or, perhaps even worse, to their students being unable to carry out their learning and assessment in the intended way. Resistance, too, can come from a perception of “unnecessary” technology – the idea that the platform one is asked to engage with is not, in fact, worth using at all, and some other, often unidentified, way would be significantly better. I offered to meet academics from the School as widely as possible – some wished to meet individually, to express concerns, or run through their questions with me, and I was also invited to regular teaching committees and special meetings. As the platform was new to my institution, no central guidance currently existed. Usually, this might have been a hinderance to me, but in this instance, because the assessment design was so specific, requiring a very particular workflow, and utilising only a small subsection of the available tools in the platform, the lack of central resources meant that the only resources available to academics and students were those I created myself. Whilst this meant I had to be careful to ensure my guidance was solid – and I certainly ran my guidance past others before sharing it, in order to be as accurate as possible – it also meant that my learners could only access guidance that was tailored specifically to them, and their assessment, and avoided confusion with pathways and workflows not relevant to the assignment at hand. Further, as I needed to fully understand the platform myself in order to create the demonstrations, creating these resources consolidated my own knowledge and practice, and helped me focus on the specific attributes required for this project. Understanding the students was not only important for myself, but to demonstrate to academics that I understood their students. I created a video from the student perspective, describing the pros, and cautions of the interface. This would differ from the student resource, but would indicate that I understood the student requirements to the academics, and thereby gain their buy-in, too. (Evidence 2: Student View Tour). In its own, rather meta way, understanding the need to demonstrate my understanding of the students is possibly the best demonstration of the way in which I came to understand the academics involved in this project. At any point, their true concern was always their students, and whilst they did experience some resistance as a result of their own digital identity and experience, I found that personal concerns could generally be assuaged by illustrating ways in which this platform could be an easy option for students, and could provide the best possible resolution to a difficult situation, in a difficult year. The first student-facing session I led went well – around 60% of attending students practiced submitted to the test inbox I’d created, and almost all said they had at least logged into the platform. The most interesting note from this was the one thing I’ve had in common with almost all new platform demonstrations I’ve done, including in my previous Learning Technologist work – a fresh instance of the single sign-on required the institutional login to be typed in correctly, or, conversely, the correct login to be remembered by the user’s browser/Keychain. We had at least a dozen students in the first session find themselves in an administrative pickle, whereby their Keychain had retained an outdated password, or they had simply forgotten their current login. From then on, I began my introductory sessions with a discussion of the login credentials, a recommendation to check you could log in before the inbox even opened, and, where briefing sessions were taking place well in advance of the actual assessment inbox having been created, setting a date ahead of time in their calendars to refresh their institutional credentials, and update their password managers. I also created a short video about logging in, to ensure that, whatever time students were trying to log in, support would be available (Evidence 3: Student Login Video). The single most difficult aspect of this project was a misunderstanding that arose only at the point of the assessment itself. I had understood that the platform would accept unlimited files, at a maximum of 5GB each. The fact of the setup, however, was that it would accept unlimited files at a *total* of 5GB. I had to spend some time unpicking how I came to this incorrect conclusion, thinking through conversations I had had both with the project team, and with the students and academics. Whilst 5GB would, realistically, have been sufficient, it was not what students had been told, and therefore this came to my attention when a Media student, having uploaded the first of 3 3GB video files, started to receive an error message. I was able to quickly put together a workflow solution for affected students, and to deploy and support this immediately. As they had their files ready, and all under 5GB, they were able to submit them to the institutional video upload platform, and to share links to these videos in the document they submitted to the assessment platform. The students were relatively unphased, and the academics seemed, if anything, to be impressed that a workaround was so quickly created, and, moreover, that I was ready and willing to handhold students through this process. The outcome of the assessment was that 100% of students submitted successfully – a statistic I’m not sure I’ve ever known on a reasonably-sized programme. It is perhaps less surprising given that, in order to progress with, or complete the course, submission must be made, but, regardless, there remarkably few issues on deadline day, and none that could not be swiftly resolved. With the student work collected, I needed to ensure the academics could access and mark the work. I led several sessions with different discipline and year groups, and at several points had to remind them that the complexities they were experiencing were as a direct result of their students having followed the assessment brief. These included:

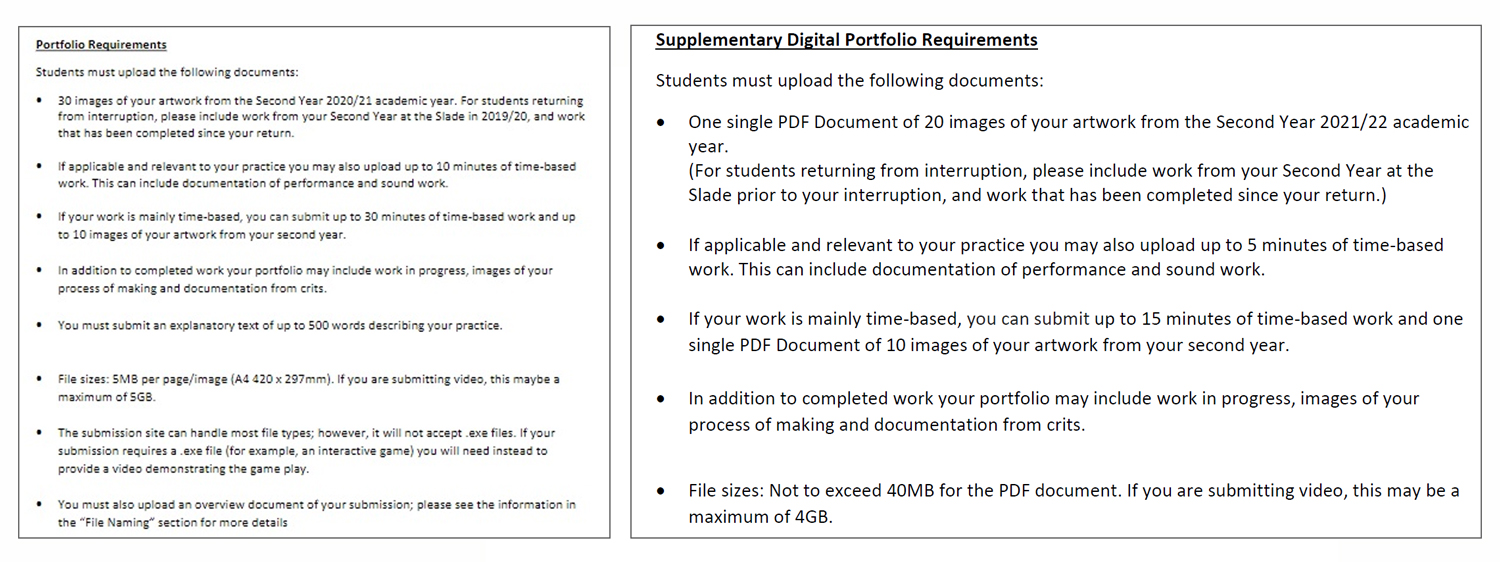

Much of my handling of these issues at this time was couched in respect for the fact that the primary instinct of the academics when creating the original assessment brief was not to restrict the art and artwork that students were creating: however keen I was to stress to the academics the consequences of this freedom for the barriers they would face when it came to marking, the insistence was that students should be able to submit as they wished. I found solutions for most scenarios, and the School made rooms available in Covid-compliant ways so that those who truly couldn’t view submissions were able to come in to the Art School and complete their marking there. Everything was done in the allotted timeframe, and I did manage to secure some written evidence (internal-only) around the issues that academics had had. This evidence ensure that, when we came to run these assessments again in 2021/22, the technical requirements were significantly changed to ensure that the issues academics had were not repeated (Evidence 4: Assessment Brief Comparisons). I created fresh resources for this year, encompassing a new and simplified login process, and outlining the new, slightly more restrictive, guidelines, which both avoided the issue with oversized files, and asked students to prepare their work in smaller, more accessible formats (Evidence 5: 2022 Student Video Submission Guidelines). In 2021/22, the Art School contacted me about numerous further projects, using other platforms for learning and assessment, and my connections to the department were significantly improved by the understanding I had gained of their practices, and concerns. The fact that I had provided training to every student in the school in 2020/21, meant that supporting second and third year cohorts in 2021/22 was rather easier, both for the students, and for myself. Reflection:I have learnt a lot from the fact that I was unable to fully test all aspects of the platform (for the simple reason that I did not have the functionality, working from home, to upload multiple files over 5GB myself). I had realised that I had something of a gap in my ability to crash test the design and setup we had, but the testing I did do led me to assume that, well, my assumptions were correct. This was a sturdy lesson for me in taking on all aspects of a new platform myself and, were I to find myself in such a situation in future, I would absolutely road test every element of an assessment brief at its limits, in order to ensure I didn’t miss such a thing. I so also think that the extent to which the functionality of this platform fell to me was a hazard of Emergency Remote Teaching – since this time, my institution has added several Digital Assessment Advisors, one of whom I now work closely with, and an incident like the above, where I was a single point of failure, would not, I believe, recur in this environment. However, and, most importantly for this section, the outcome of this misunderstanding was not all bad – the academics involved in my construction of the workaround were very appreciative of my responsiveness, and reassured by my ability to develop and support solutions. If anything, having seen, to their mind, the technology “fail”, and to see this be managed and mitigated, increased their confidence in both my ability to support their students, and overall increased their willingness to work with me on future projects. Further, as my solutions continued to use institutional platforms they would have been able to be supported by core teams if it had come to it. As I made the academics involved aware of this, they became, too, aware of the amount of support the central university had. Having been so separate from the central institutional support by not using the majority of the central teaching and learning platforms up to this point, there was perhaps a sense that such support was not available for the Art School – when, in point of fact, they would always have been welcome to work with such technologies. I learnt a great deal about understanding the context and experience of my learners whilst working on this project. The point about the extent to which academics believed they would put up with any inconvenience in the name of their students having the experience they believed their students ought to have…until they realised that these inconveniences could, in fact, jeopardise their ability to assess the work in the way it needed to be assessed, was a difficult one for me to handle, as it seemed that the academics truly did need to go through those inconveniences to understand them. In subsequent deployments of this assessment platform, I have created marking experiences for academics to test at a much earlier point in creating the assessment – the capacity of the platform to accommodate all types of submission means, I believe, that it is only sensible to use the academic user experience as being just as valuable. I also learnt from this that every element of the lesson at hand is important, including the ways in which the student needs to interact with the technology in which their assessment will be conducted. Further, with current students having had such a wide range of experiences with technology as a result of ERT, scaffolding a session to introduce them to the technology, even if only to give them an opportunity to log into it and see around, can go a very long way to reassuring students that the platform won’t ambush them when it comes to the point of submission. Finally, knowing what support looks like is not an experience every learner has had. At any point of introducing myself to a class, a new academic, or department, I ensure that I outline how support can be obtained, whether from myself or central services, and that a reasonable timeline for this support is part of that communication. Evidence:1. Case Study of Module Redesign:Click to view.

2. Student View Tour for Academics: https://mediacentral.ucl.ac.uk/Player/eIdhIdEG3. Student Login Video: https://mediacentral.ucl.ac.uk/Player/jDg1bH3d4. Comparison between Assessment Brief 2020/21 and Assessment Brief 2021/22:

5. 2022 Student Video Submission Guidelines: https://mediacentral.ucl.ac.uk/Player/IdGgf74D |

|||

|